The Command Line Interface

Contents

Environment

A command line, or more technically, a command line interface (CLI), is a text-based method of interacting with a computer. CLIs were the original way to interact with computers, before there were mice or touch pads. It may seem archaic, but it's actually a very efficient, time-tested way to interact with your computer, at least when you're programming.

The most popular command line command sets are based on the Unix operating system. Today's Linux systems shadow Unix and Mac OSX actually runs on top of Unix. Windows' has a few options for CLIs: the DOS (Disk Operating System) Command Prompt (built in), PowerShell (built in), and third-party tools like ConEmu (which we'll be using).

Now, lets get you set up so you can see what we're talking about. Following the directions below based on your operating system.

Windows setup

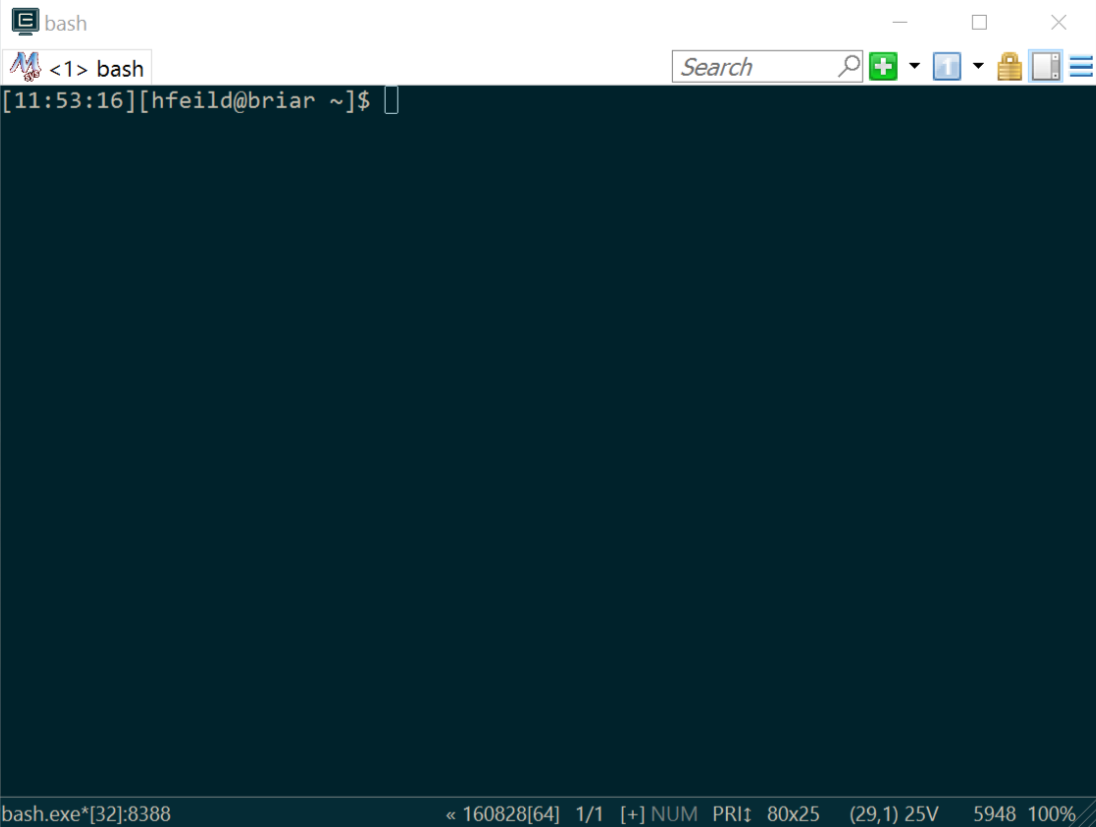

If you have not already installed ConEmu, please follow these directions to do so. Once installed, open ConEmu, which should bring up something that looks like:

Look for a blinking block character; it should appear just to the right of the

$ character. The blinking block is called the cursor and the text to the left (in the screenshot above,

the text [05:50:42][Henry ~]$) is called the command prompt, or prompt for short. Your prompt will

probably look different—I've specifically set mine to appear the way it

does.

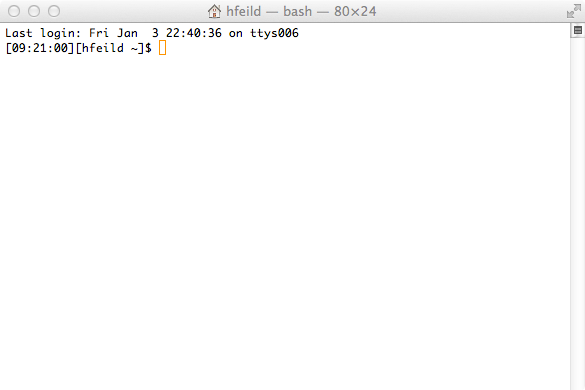

Mac OSX setup

In Mac OSX, search your applications for a program called Terminal. Spotlight is

probably the easiest way to search for it—you can open Spotlight by

pressing the key combo Command+Spacebar. A search box

should appear in the upper right corner of your screen. Type "Terminal" and

select the Terminal application from the search results. When opened, it should

look something like this:

Look for a filled rectangle; it should appear just to the right of the

$ character (you may have a different character). The filled

rectangle is called the cursor and the text to the

left (in the screenshot above, the text [09:21:00][hfeild ~]$) is

called the command prompt, or prompt for short.

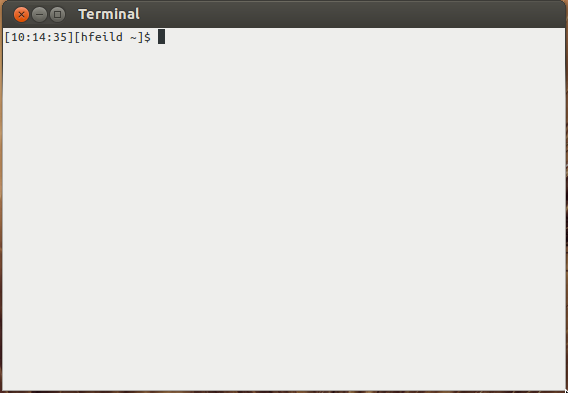

Linux setup

There are lots of Linux variants. If you're using linux, you probably know how

to open a terminal. For this example, lets suppose you're running Ubuntu. Press

the key combo Ctr+Alt+T or search

applications for Gnome Terminal. You should see a window like the following:

Look for a blinking, filled rectangle; it should appear just to the right of the

$ character (you may have a different character). The blinking

rectangle is called the cursor and the text to the

left (in the screenshot above, the text [09:21:00][hfeild ~]$) is

called the command prompt, or prompt for short.

Basics

Now that you know how to access a CLI on your system, lets use it! One thing you want to always keep in mind is, you cannot use your mouse with a CLI—it's entire keyboard based. To move left and right, you need to use the left and right arrow keys. This can be tedious, but you'll soon grow accustomed to it.

Lets start by considering what the CLI is. It's really a way to run programs and navigate through your file system. So in many ways, it's a glorified, text-based File Explorer (e.g., Mac Finder or Windows Explorer). Most of the commands we will learn about are programs that will help you navigate your file system.

pwd

The first command we'll learn about is pwd, short for "path to working directory". At your CLI prompt, type in pwd.

You will get a path to your current folder (called a directory in CLI-speak),

like this:

$ pwd

/Users/hfeild

$ pwd

/c/Users/hfeild

Note: I will use orange to represent what text I typed in the terminal versus text I did not enter.

A path is a sequence of directories, separated by

forward slashes.

Path's come in two forms: absolute and

relative. Absolute paths start with the root directory.

On Unix-based systems, the root is a single

slash: /. In ConEmu on Windows, it is the drive letter, usually

/c/ (paths that start with another drive letter are also absolute

paths, e.g., /e/ for the E: drive).

The path displayed by the pwd

command is an absolute path. It tells us exactly what set of directories we need

to follow from the root to get to the current directory the CLI is sitting in.

We'll learn about relative paths in a couple sections.

ls

Knowing the path to the current directory is great, but what if we want to know

what files and subdirectories reside in the current directory? We can list these

by using the ls command (list directory

contents). Here's what it looks like:

$ ls

Applications Google Drive Public Win7Shared shared

Desktop Library Qt bin tmp

Documents Movies Sites csc160

Downloads Music Ubuntu One foo

Dropbox Pictures VirtualBox VMs research

Note that your files and sub-directories will differ.

You can more detailed information about files and directories by passing the

-l flag to the ls command, like this:

$ ls -l

total 8

drwx------ 4 hfeild staff 136 Dec 20 11:42 Applications

drwx------+ 20 hfeild staff 680 Jan 3 22:40 Desktop

drwx---r-x+ 16 hfeild staff 544 Dec 23 09:32 Documents

drwx------+ 45 hfeild staff 1530 Jan 4 10:09 Downloads

drwx------@ 20 hfeild staff 680 Jan 2 17:24 Dropbox

drwx------@ 21 hfeild staff 714 Dec 23 11:00 Google Drive

drwx------@ 56 hfeild staff 1904 Jan 3 13:17 Library

drwx------+ 4 hfeild staff 136 Oct 25 00:20 Movies

drwx------+ 4 hfeild staff 136 Sep 15 16:01 Music

drwx------+ 8 hfeild staff 272 Dec 11 09:07 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x+ 4 hfeild staff 136 Sep 6 09:23 Public

drwxr-xr-x 13 hfeild staff 442 Dec 23 09:23 Qt

drwxr-xr-x 10 hfeild staff 340 Dec 14 16:36 Sites

drwxrwxr-x 8 hfeild staff 272 Sep 29 10:51 Ubuntu One

drwxr-xr-x 4 hfeild staff 136 Sep 7 10:50 VirtualBox VMs

drwxr-xr-x 29 hfeild staff 986 Jan 4 09:20 Win7Shared

drwxr-xr-x 15 hfeild staff 510 Dec 23 07:57 bin

drwxr-xr-x 6 hfeild staff 204 Dec 1 21:29 csc160

drwxr-xr-x 4 hfeild staff 136 Dec 14 15:40 foo

lrwxr-xr-x 1 hfeild staff 32 Dec 14 20:03 research -> /Users/hfeild/Documents/research

drwx---r-x 5 hfeild staff 170 Sep 20 08:38 shared

drwxr-xr-x 2 hfeild staff 68 Dec 15 21:31 tmp

The -l flag is an example of what we generically call a command line argument or command line

parameter (we'll use argument and parameter interchangeably). Command

line arguments are whitespace-separated strings passed to a command (in this

case, ls). You can pass in as many arguments as you want, though

its up to the program whether or not it uses them, or it may even fail with an

error that an argument you passed in is unrecognized. We'll see some other

examples of command line arguments.

You can also pass in absolute or relative paths to ls. For example,

to list all of the files in /Users, we can do the following:

$ ls /Users

hfeild

$ ls /c/Users

All Users Default Default User Henry Public desktop.ini

cd

The cd command is short for change directory. You can invoke it without any commands, in which

case you will end up back in your home directory (e.g., on my Mac, that's

/Users/hfeild) or you can pass it a relative or absolute path as a

command line argument. For example, to change into /Users on a Mac,

we can type:

$ cd /Users $ pwd /Users

By entering the command pwd right after cd, we can see

that the working directory has been changed to /Users. From here,

if we type cd without any arguments and then check the path to the

working directory again, we'll get:

$ cd $ pwd /Users/hfeild

Lets talk about relative paths for a minute. Relative paths are paths that are

relative to the working directory. So looking at all of the directories listed

in my home directory, I can change into one of them by just supplying the

directory name. E.g., issuing the command cd Desktop from my home

directory will change me into /Users/hfeild/Desktop:

$ cd $ pwd /Users/hfeild $ cd Desktop $ pwd /Users/hfeild/Desktop

Relative paths can consist of more than one nested directory. For example, lets

say that inside of my Desktop directory, I have a subdirectory

named notes. The absolute path would look like:

/Users/home/hfeild/Desktop/notes; the relative path from my home

directory would look like: Desktop/notes. This example should shed

some light on it:

$ cd /Users/hfeild/Desktop/notes $ pwd /Users/hfeild/Desktop/notes $ cd $ pwd /Users/hfeild $ cd Desktop/notes $ pwd /Users/hfeild/Desktop/notes

To drive home the point, absolute paths can be used to navigate to a directory no matter the path of the current working directory. Relative paths, however, must be relative to the current working directory.

A nice little shortcut is the use of ~ (called a tilde, and pronounced "til-da") in place of the path of your

home directory. So, on the command line ~ is equivalent to

/Users/hfeild in Mac OSX, C:\Users\hfeild in Windows,

and /home/hfeild in Linux. E.g.,

$ cd ~/Desktop/notes $ pwd /Users/hfeild/Desktop/notes(Back to top)

Advanced navigation

There are many relatively common features of CLIs that make navigating a breeze. We outline some of them here:

- \ref. Canceling a command

- \ref. Command history

- \ref. Tab completion

- \ref. Copy/Pasting

- \ref. Home/End/Back/Forward

Canceling a command

Sometimes you may find that you've started typing something on the command line

and then decide you'd like to start over. You could just backspace all the way

back to the beginning, but that's a lot of work. You can delete the whole thing

by using the key combo Ctrl+c. That will cancel your

old command. This is also the combo you use to quit a program that's running

(you might need to use it when you run one of your own programs).

Command history

Your CLI will keep track of your recent command history. To cycle through your commands in chronological order, use the up and down arrow keys. Every time you hit the up arrow, you'll go back another command in your history. Hitting down will go forward one command.

Tab completion

It can be annoying and tedious to have to type everything out, especially if you

are trying to change into a directory with a long path. Luckily, most CLIs have

something called tab completion. As you start to type

a command or a path, just press the tab key and you'll start

getting suggestions. This behaves a little differently in Linux/OSX than in

Windows. In Linux/OSX, tab completion will do one of two things: 1) complete the

command or directory name for you or 2) if there is more than one command or

directory name, that shares the same prefix, it will complete up until the point

where one of them diverges. In the latter case, you can double-tap

tab again to see all the options (they'll be printed to the

screen).

Here's an example. Say that My desktop contains the following subdirectories:

$ ls ~/Desktop

notes classes-2013 classes-2014

If I want to change into the notes directory, then you can start

typing cd ~/Des, then hit tab. In Linux/OSX, you

should now see cd ~/Desktop appear (i.e., ktop is

automatically filled in for you). Keep typing, adding in /no, then

hit tab again. You should see the tes letters appear,

giving you cd ~/Desktop/notes.

Now lets say you want to go into the classes-2014 directory. Notice

that there's another directory with the same name up until the last character.

If we type in cd ~/Desktop/c and then hit tab, we'll

get the following: cd ~/Desktop/classes-201. The CLI doesn't know

whether you want the one with the 3 or 4 at the end, and it doesn't bother

guessing. Lets pretend that you didn't know what the options were. You can

double-tap the tab key. That will give you a list of options. In

our case, it'll look something like this:

$ cd ~/Desktop/classes-201

classes-2013/ classes-2014/

Now you can type the remaining character.

Windows handles tab completion a bit differently. First, it will auto expand

your path (so ~\Desktop becomes

C:\Users\hfeild\Desktop). Then, it will choose one of the files or

subdirectories that matches the prefix you gave. You can cycle through options

by pressing tab again.

Copy/Pasting

Copying and pasting is different on each system. Mac is the simplest, as it uses

the same short cuts as every other Mac app: Cmd+c to

copy and Cmd+v to paste.

Linux requires you use Ctrl+Shiftc to

copy and Ctrl+Shiftv to paste.

In ConEmu, you can copy text by highlighting the text you want to copy, then

clicking away from it. To past text, right click or use

Ctrl+v.

Home/End/Back/Forward

Navigating a long command can be tricky. Here are a few nice shortcuts for moving within a line in a CLI:

- Home (Windows/Mac/Linux) or

Ctrl+a(Mac/Linux) moves to the beginning of the line - End (Window/Mac/Linux) or

Ctrl+e(Mac/Linux) moves to the end of the line Ctrl+←(Windows/Linux) orAlt+←(Mac) moves to the beginning of the previous word/stringCtrl+→(Windows/Linux) orAlt+→(Mac) moves to the beginning of the next word/string

Some of these may not work all of the time. If you're having trouble, search the Web for a workaround.

(Back to top)Common commands

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

cd |

E.g., cd ~/DesktopChanges the working directory to the specified directory. Directory paths can be absolute or relative. If no arguments are given, the destination path is assumed to be the user's home directory ( ~/). |

ls |

E.g., ls ~/DesktopLists the files and subdirectories of the specified directory. Directory paths can be absolute or relative. If no arguments are given, the contents of the working directory will be listed. To list information about each file/directory, include the flag -l: ls -l

~/Desktop. |

pwd |

E.g., pwdDisplays the path of the working directory. |

mkdir |

E.g., mkdir ~/Desktop/notesCreates a new directory, if it does not exist. The path of the new directory can be relative or absolute. Multiple paths can be included as separate arguments. To create all directories on the path that do not yet exist, include the -p flag: mkdir -p

~/Desktop/notes/a/b/c. |

cp |

E.g., cp program1.cpp program2.cppMakes a copy of the first listed file ( program1.cpp in the example) and

gives it the name of the second argument. You can copy multiple files

and directories into a destination directory by using the

-R flag (short for recursive),

listing all of the files/directories to copy, and ending with the

directory to copy into, e.g.: cp -R ~/Documents/notes program1.cpp

~/Documents/notes2. |

mv |

E.g., mv program1.cpp program2.cppRenames the first listed file (or directory) ( program1.cpp in the

example) and gives it the name of the second argument. You move multiple

files and directories into a destination directory by listing all of the

files/directories to move, and ending with the directory to move into,

e.g.: mv ~/Documents/notes program1.cpp

~/Documents/notes2. |

Exercises

- In your operating system's file viewer (e.g., Finder on Mac or Windows

Explorer), create a subfolder in your

Documentsfolder namedcommand-line-exercises. Now open your CLI and navigate to that directory. Issue thepwdcommand. What do you see? - Using the CLI and not Finder/Windows Explorer, create a new subdirectory

in the

command-line-exercisesdirectory namedexercise-2. Now open Finder/Windows Explorer. Do you see the directory you just created with from the command line? - Create a blank text file (using Notepad/TextEdit/Sublime Text/jEdit) and

save it in the

command-line-exercisesdirectory asexercise-3.txt. From the CLI, list the files in thecommand-line-exercisesdirectory and see if the text file is there. - Using the CLI, copy the

exercise-3.txtfile into theexercise-2subdirectory. List the contents of that directory to make sure it's there. - Using the CLI, rename the

exercise-3.txtfile in the maincommand-line-exercisesdirectory toexercise-5.txt. List the contents of thecommand-line- exercisesdirectory to see if the renaming was successful.