A "Feild" Guide to Programming with C++

Introductory programming notes by Henry FeildChapter 1: Planning Software Projects

Important takeaways

- Know what you're programming before you start: What's the program's purpose? Who are the users? How will users communicate with the program? What are valid and invalid inputs?

- Plan before you begin coding using sketches, flow charts, and pseudo code

- Start programming like a construction team builds a house—start with the structure (what we call a skeleton) then incrementally add the details (implement pseudo code with real code)

- Compile and test along the way—don't wait until the end

- Not sure how to implement something? Make a small test where you only worry about playing around with that one idea

Contents

Motivation

Many people's first instinct when confronted with a programming task is to jump right into the source code. That's generally a bad idea. Why? Because it requires you to make things up as you go, which has several negative consequences, especially when projects get larger.

- First, you end up not really knowing where you're going, making it difficult to estimate how long it will take or what challenges you might face. It's hard to fully grasp the big picture without knowing what the big picture is.

- Second, you will most likely have to redo a lot of your work. Inevitably, you'll wind up in a situation where it becomes clear that something you already implemented is, in fact, not going to work for some reason.

There's an easy solution to this, though programmers, especially new programmers, try to avoid it: planning (gasp!). Planning provides an extremely useful way to take what can sometimes be an overwhelmingly large and complex project and break it into substantially smaller chunks, allows you to maintain a view of the big picture during the entire development process, and will make debugging (the process of fixing your code when it doesn't work as expected) substantially simpler.

I recommend you follow the topics outlined below roughly in order. However, software development is an iterative endeavor, and so you will likely have to use a combination of these topics, going back and fourth between them as problems are encountered or new requirements crop up.

(Back to top)Program sketching

To start with, let's assume you have an idea of what your program needs to do. For example, if we are programming a calculator, then we know it should calculate some set of operations on numbers and spit out the answer. We can use a sketch to help us organize our thoughts about how the calculator will look, feel, and behave.

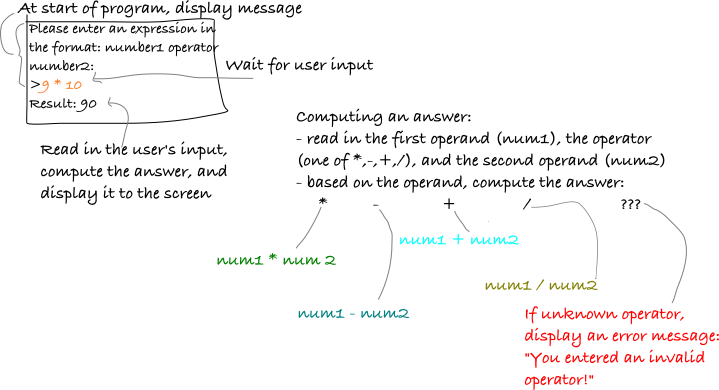

A sketch can be super informal. Here's one sketch I made of the calculator. This is for a command line calculator (so there is no graphical interface with buttons, etc.):

As you can see, I have sketched out the terminal window in the upper left. I included the text that the program displays in the terminal, an example of how user input will be entered, and an example response. I've included labels to help me and anyone else who sees the sketch understand what's going on. On the right side, I've included the gist of program's steps and how it will behave based on different user inputs.

You should do some sort of sketch for every program you write. Aside from helping you think through your program, it's an important aide when seeking help because you can show your sketch to someone to communicate what it is you are trying to do.

Requirements and use cases

With any software project, it is crucial to establish what the requirements are. What is the input suppose to be? What's the output suppose to be? How should the output be formatted? What restrictions are there on the implementation? In a programming class, the requirements are often given to you, but that's not always the case, and even when it is, there are usually missing or inferred requirements that you must think about. To start with, make a list of all the requirements.

Once you have the requirements listed, make a set of use cases. Use cases are examples of how the software will be used and includes specific input and desired output. Use cases can be used to verify that your final project is working as expected. The most crucial thing here is to make enough use cases to uncover any bugs that may exist.

Consider the example of a simple calculator program. It allows the input of decimal numbers and operations between them (+, -, *, /) and should output the result of the calculation. We may list our requirements as follows:

- input in the format:

<number 1> <operator> <number 2> - output in the format:

Result: <result> - output must be the result of applying the given operator

(

<operator>) to the two inputed numbers (<number 1>and<number 2>), in the order they were entered.

Some use cases are:

- input:

10 - 3, output:7 - input:

5 * 3, output:15 - input:

3 / 2, output:1.5 - input:

4.5 + 16, output:20.5

Program flowcharts

One option for moving along is to create a program flowchart. A flowchart is a series of boxes and arrows that indicate the steps and control flow of the program. There are many types of boxes in formal flowcharting, each with its own meaning. Many of the most common are listed in \ref.

Flowchart symbols

| — Start or end a program/procedure. |

| — Input/output. |

| — A process (usually an assignment). |

| — A decision (also called a branch or conditional). |

| — A subprocess (e.g., a function invocation). |

| — Joins multiply flow branches back together. |

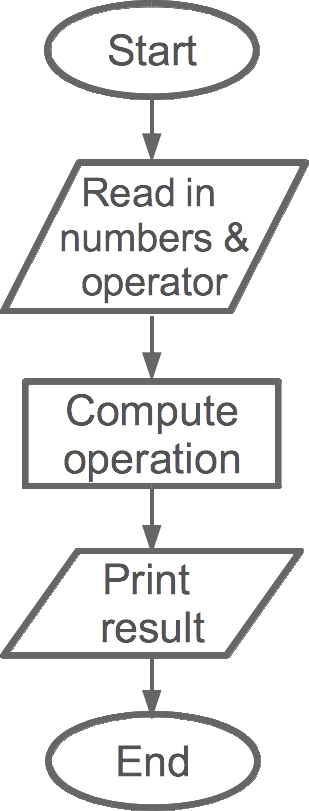

Flowcharts do not have to be perfect when you're just sketching out the flow of your program. Consider this an iterative process, and one that is geared to help you think through how to ultimately implement your program as code. For example, \ref shows a high-level, simplistic view of our calculator. It's high level because we don't actually describe how data should be read in in the first parallelogram nor how we should compute the operation. The latter is especially vague, since "compute operation" actually encapsulates several steps, including determining which operator was entered. However, this is a great and simple start to thinking about how the more complex parts will be computed.

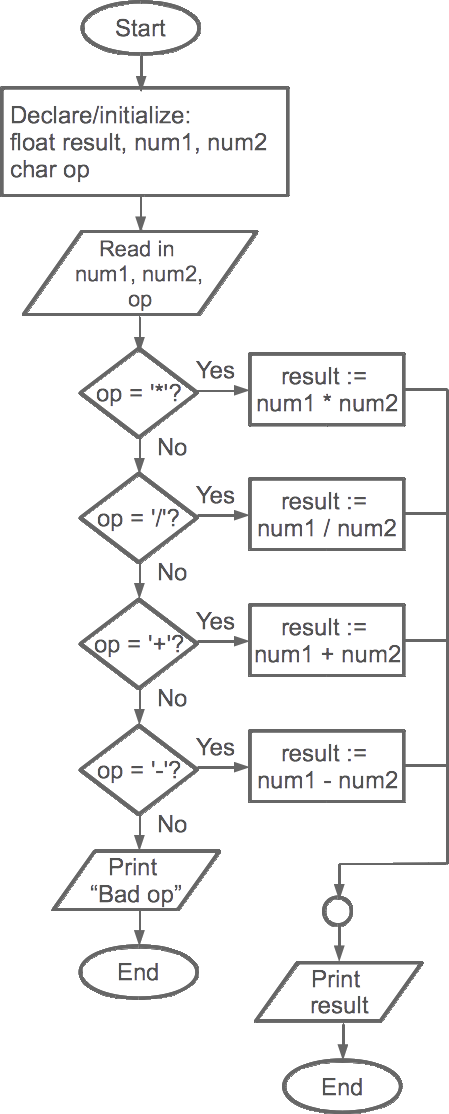

We can refine this simplistic flowchart and add in the details, as shown in \ref. Here we've stated what

kinds of variables we need, what's being read in, and we've used branching to

test which character the operator is. Based on the value entered for

op, we will carry out the specific operation. We even have error

handling—if op is not one of *, /, +, -, we print an error

message and end the program. If op is valid, then after we carry

out the operation, we join all of our branches together and display the value we

computed and stored in result.

See this page for more details on flowchart symbols. This video provides some examples of flowcharts.

(Back to top)Pseudo code

Flowcharts are a good way to visualize the flow of control throughout a program without relying on a particular programming language. Another helpful tool that looks a bit more like code, but is still independent of a particular programming language, is pseudo code. It's called pseudo because it reads a little bit like code, but there is no standard syntax—it's completely up to you. This can make the process a bit opaque, especially in class, because it's unclear when you've "done it right". However, this overview should help you out.

Pseudo code should generally be in English, rather than C++ (for example). This allows your pseudo code to be implemented in different languages. Just like in flowcharting, we can write pseudo code that is very simplified (high-level) or very detailed (low-level). In the end, you want something that is lower level, where each step can be written as one or two lines of code in the target programming language.

Here's an example: let's suppose that we want to write the pseudo code for our calculator example. The first iteration might look something like this:

Calculator: 1. read in two numbers (can be decimals) and an operator from the user 2. compute the result by applying the operator to the two numbers 3. display the result

We can expand this a little to make the beginning steps clearer and to explain how to compute the result. For example:

Calculator:

1. initialize variables: num1, num2, and result (decimals);

operator (single character)

2. prompt user and read in num1, num2, and the operator

3. compute the result by applying the operator to the two numbers:

a. if the operator is *, set result to num1 * num2

b. otherwise, if the operator is /, set result to num1 / num2

c. otherwise, if the operator is +, set result to num1 + num2

d. otherwise, if the operator is -, set result to num1 - num2

e. otherwise, the operator is invalid -- display an error message and exit

4. display the result

The line numbers are not necessary, but you may find them helpful. You could get more specific, such as writing out exactly what will be printed when prompting the user (e.g., display the prompt: "Please enter two numbers and an operator"). I would say the level above is sufficient, but adding additional details is okay, provided they are not programming language specific.

Check out this video for more information about pseudo coding.

(Back to top)Skeletons, stubs, and incremental implementation

As mentioned, flowcharts and pseudo code are largely programming language agnostic, meaning they aren't tied to a single programming language. For example, we could take our calculator flowchart and implement it in any of a number of languages—C++, Java, C, Ruby, Python, etc. To move from something abstract like a flowchart to actual code, I recommend starting with a program skeleton consisting of stubs filled with pseudo code and then incrementally implementing the stubs, being sure to test your code along the way.

A skeleton is a set of code that is usually just an outline without the core bits of logic implemented. All (or most) of the required functions and methods should be present, but their bodies will be empty. Functions (we'll cover what these are in a later chapter) with a return type should return a dummy value of that type. Importantly, the program should compile and run at this stage, even though it won't do anything useful. Let's consider a sample skeleton for our calculator program in C++.

Here we can see that I've added the header, comments, and the main

function. The function doesn't do anything, though, other than return 0. Notice

that the comments at the top of the file and above main describe

the overall program. The comments within main describe the steps to

implement in English—pseudo code. In fact, we can update this

skeleton to use the pseudo code we produced in the previous section:

This is a nice example of how useful pseudo code is. When we go to implement, we can tackle one line of pseudo code at a time, ensuring the program compiles after each is implemented. Importantly, let me point out that this program compiles and runs, though it doesn't actually do anything when it runs (all it does is immediately exit). Our next incremental step might look like this:

When you try to compile this, you will get an error. Why? Because

operator is a reserved C++ keyword, and we're trying to name a

variable after it (you can't name variables after C++ keywords; see the Variables chapter for a full list of reserved

keywords). Imagine if we had implemented the entire program without testing;

we'd have to go back and fix this everywhere we used operator.

Testing early caught it before it became systemic. Now that we've caught it,

we can change it before moving forward. Let's try naming the variable

op instead:

This compiles and runs, albeit, it still doesn't do anything interesting when it runs. But it doesn't fail. Now we can move on to implementing the next step:

This will compile, and we can run it. Here's the process on the command line:

$ g++ calculator.cpp -o calculator $ ./calculator Please enter an expression in the format: number1 operator number2: 3 * 5

So it works! Now we can carry out each of the next bits, compiling and testing along the way, until we finally reach our completed program. This might look something like the following:

One more thing about stubs. Though we haven't learned about functions in general, once we do, it'll be helpful to see how this example might look with function stubs. Again, stubs are functions that have the correct outside appearance (i.e., name, return type, and input parameters), but have only comments and place holders for internals. Let's say that we wanted to add a helper function that would carry out the actual computation. It would take the operands and operator, and return the result. Here's the skeleton:

(Back to top)Sandbox

One of the most helpful things I do when I develop is to test out things that I'm not sure about with really simple examples. I do this in what I call a sandbox—a folder on my computer that I can just play around in. The short programs I write don't have to do anything, they're just a way for me to explore syntax or try something out in a small, controlled environment before spending the time to implement it in a full scale project. I recommend that you create a sandbox directory and do exactly that as you work on your programming assignments.

(Back to top)